Can I say that in class? Best practices for college instructors

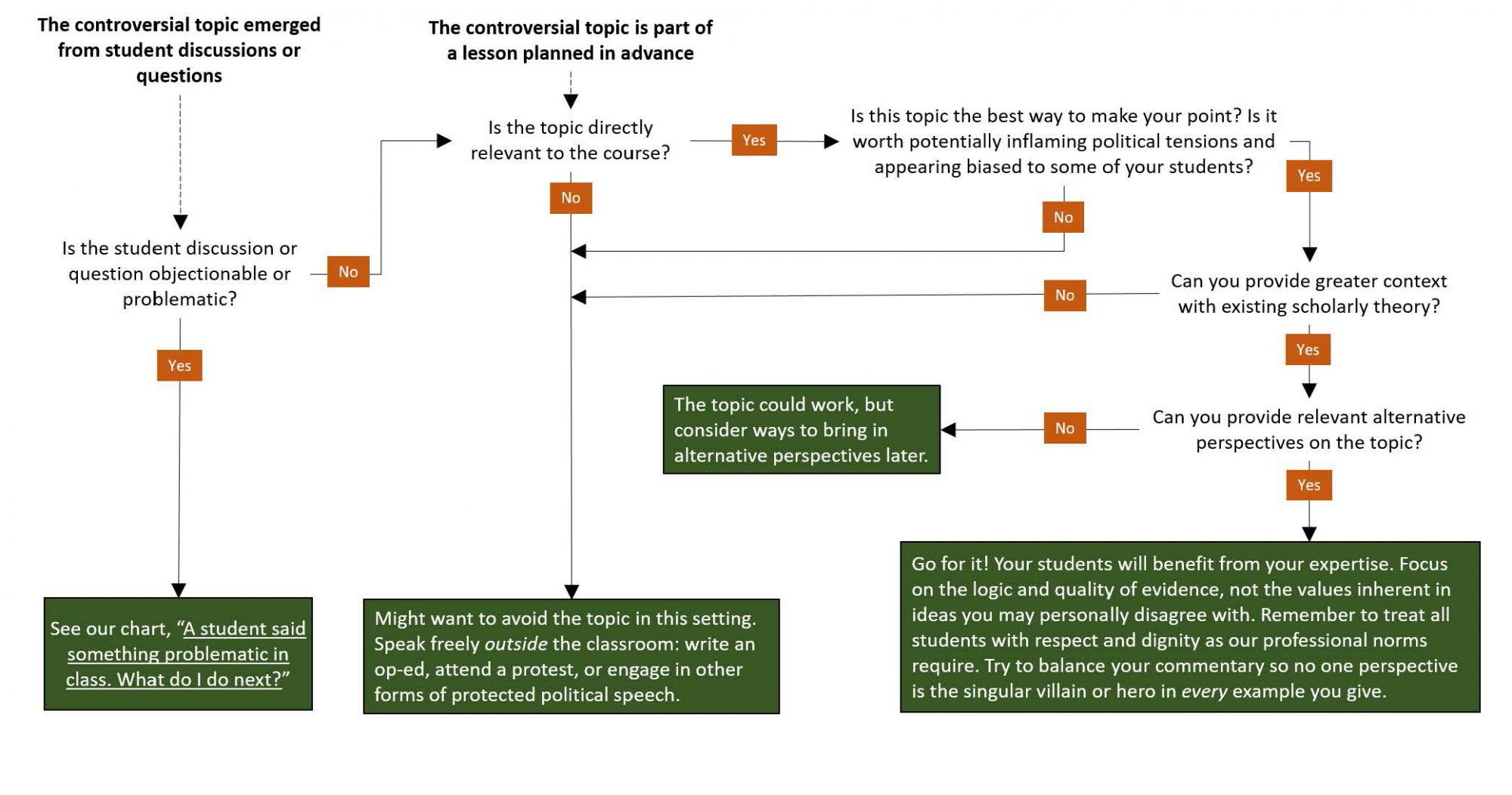

Situation: You want to address a controversial political, inflammatory, or sensitive topic in front of your class.

The College of Liberal Arts supports you in teaching and speaking on controversial issues as appropriate.

A student said something problematic in class. What do I do next?

Is the statement relevant to the class topics?

- Make it a teachable moment: Start a class conversation about different perspectives or views related to the statement

- Provide relevant counter-examples, facts, and evidence to demonstrate the value of multiple, alternative perspectives

- Ask the student to provide additional clarification and evidence to foster discussion

- Invite other students to provide alternative information and perspectives

- If the statement is irrelevant, explain that the statement is off-topic, and ask the student to address it outside class with you instead

Do other students (or you) feel extremely distressed or angry at the statement?

- Consider carefully if the statement is relevant, valid, and part of students’ right to listen critically and challenge a professor’s opinions

- Emphasize the value in listening to and discussing a range of relevant viewpoints, even when one perspective is distressing

- Reiterate the CSU Principles of Community and student responsibilities inside and/or outside class

- Discuss the impact of the statement as a class discussion, perhaps waiting until the following week or class session

- While protecting the student’s privacy, address one-on-one with concerned class members as needed

- Outside class, discuss the situation with a trusted faculty member in your department for feedback and other perspectives and review the CSU Student Conduct Code

Is there threatening, abusive, discriminatory, or harassing language or behavior? Or are there disruptive/concerning statements consistently over time?

- In class, stop the conversation and explain that the CSU Student Conduct Code and the CSU Discrimination Policy has policies against these types of language and behavior.

- After class, discuss the situation with a trusted faculty mentor, course coordinator, or a member of the Open Door Pedagogy Network in your department for feedback and other perspectives.

- Inform your chair about the behavior in an email to be sure you document the situation well.

- Schedule a meeting with the student one-on-one to discuss why the behavior is disruptive or concerning. If the incident could result in university sanctions for the student or for you, invite a colleague to the student meeting with you as witness.

- Document your account of the meeting afterwards in an email to file.

- If needed, meet with your chair and the student after the initial meeting to follow up.

- If the issue is still unresolved, you can work with Student Conflict Resolution to identify next steps.

What not to do:

- Do not ignore the statement if it’s central to class content and can help everyone learn

- Do not engage in email exchanges with the student about it

- Do not ignore the student’s right to express views based on their personal beliefs or opinions without punishment

- Do not ignore the student’s right to reasoned exception and to critically challenge course content

It is biased speech against a group protected by CSU bias policy?

- Stop the conversation in class.

- After class, consider if the speech is “any conduct, speech, or expression, motivated in whole or in part by bias or prejudice that is meant to intimidate, demean, mock, degrade, marginalize, or threaten individuals or groups based on that individual or group’s actual or perceived identities.” (See the CSU policy on discrimination, harassment, etc.)

- Consult a trusted colleague or member of the Open Door Pedagogy Network to get additional perspectives, and review the CSU Discrimination Policy and the CSU Student Conduct Code.

- If the speech was biased, report it as an Incident of Bias.

Are you concerned about the student or other members of the community?

- Concerns about the student’s mental health can be referred to Student Case Management, (970) 491-8051 or refer the student to the CSU Counseling Center, (970) 491-7111.

- Concerns about other members of the campus community can be reported to to Tell Someone, or you can contact the CSU Police non-emergency line at (970) 491-6425.

- Any of these concerns should be documented fully, including any actions you took, and also reported to your chair.

If you or others are in clear, imminent physical danger:

- Call CSU Police by calling 911

- Ensure the physical safety of the class. Dismiss the class and exit the classroom space

- Inform your chair as soon as possible

- Follow up with Tell Someone

Considerations for controversial topics in the classroom

So you want to address a controversial political topic in front of your class. If it is relevant and contributes to the scholarly conversation of your classroom, go for it! Your students will benefit from your expertise and the current context. Just remember to treat all students with respect and dignity as our professional norms require.

Try to balance your commentary so no one politician or party is the singular villain or hero in every example you give. CLA supports you in teaching and speaking on controversial issues as appropriate.

Here are some considerations you might have:

(All quotes from CSU Faculty Manual section E.8.g.)

| Is the topic…? | For example… | Some considerations… |

| Beyond the course subject matter | A medieval art history course discusses the previous Tuesday’s election results because you are upset about the outcome. | Best practices advise speaking freely outside the classroom: write an op-ed, attend a protest, or engage in other forms of protected political speech. If you do inadvertently express an explicit political opinion, “make every effort to indicate that [you are] not an institutional spokes[person].” |

| Relevant, but not immediately apparent | A dramatic literature course discusses current conversations of trans* identity as a prelude to discussions of cross-gender casting in Shakespeare’s plays. | While current examples can be effective in connecting students to the past, you should provide greater context with existing scholarly theory to make connections clear and relevant. |

| Relevant and necessary | An ethnic studies class discusses examples of systemic racism in contemporary society. | Not only is the material timely and relevant to the course, it would be virtually impossible to teach the subject matter according to the current state of the discipline without these concepts. Students may take “reasoned exception” to key concepts and ideas, but are still responsible to learn the material. |

| Relevant but optional | An economics class discusses a currently debated policy (e.g. Universal Basic Income) that is useful to illustrate a point, but is not the only option for an example. | You may use relevant teaching examples that illustrate key concepts, but should “exercise appropriate restraint, and show appropriate respect for the opinions of others.” Providing both context and additional examples that occupy different political positions may be advisable. |

| Particularly partisan | A history course connects the history of voting rights with contemporary gerrymandering and polling practices in ways that express clear preference for one current party’s position. | While the historical connection may be highly relevant, any assertion of personal preference enters a grey area. Remember that in such cases, you should “make every effort to indicate that [you are] not an institutional spokes[person].” Best practice suggests also discussing examples from different political positions. |

| A matter of form | A rhetoric class explores a recent speech from a prominent politician as a case study of logical fallacies as a matter of technique. | Case studies are great for illustrating writing and argumentation techniques. Take care that your examples do not consistently skew in one political direction, and remember that “appropriate respect for the opinions of others” remains important. When using case studies, be sure to acknowledge that you are analyzing techniques rather than analyzing the subject matter. |